THE IMPORTANCE

OF CALCIUM!

HOW MUCH CALCIUM DO COWS NEED?

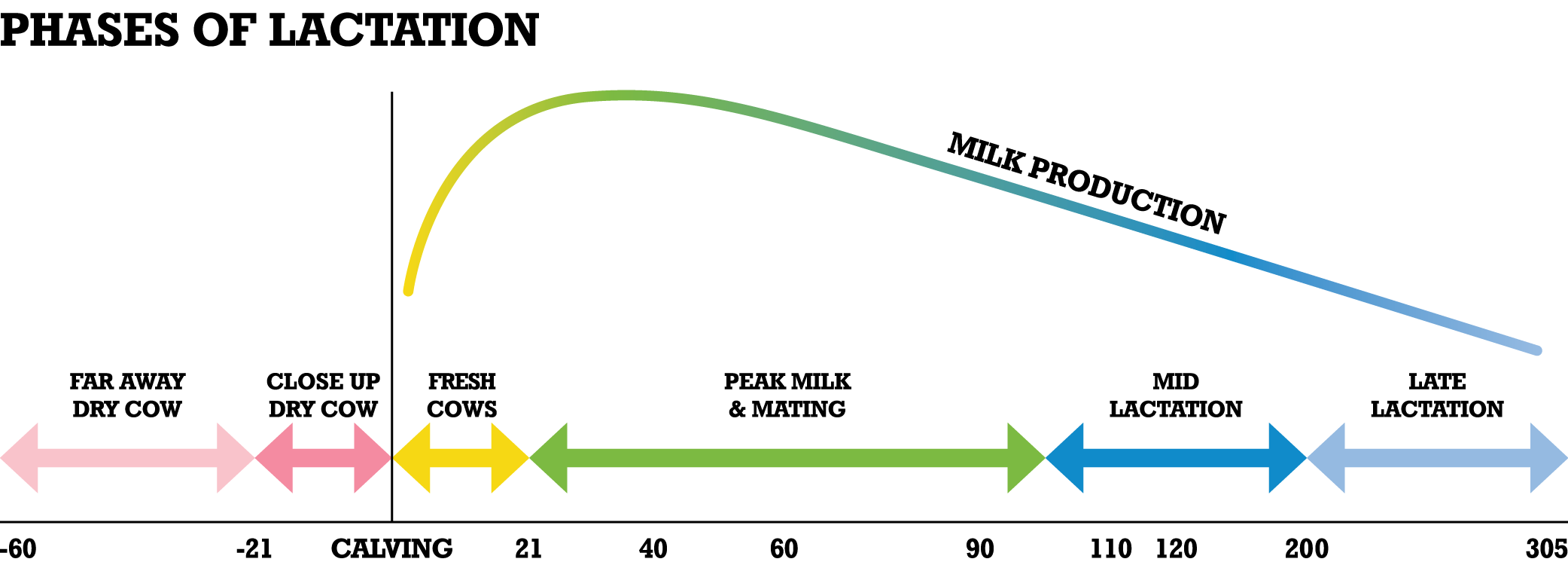

Calcium is required by all dairy cows; the amount required depends largely on the stage of lactation.

FAR AWAY DRY COW

This phase is from dry off to 21 days pre-calving. This is ‘cow down-time’. During this phase the cow should be resting and re-grouping in preparation for the upcoming lactation. She is not lactating and the nutrient demands of the foetus are relatively low. As such, the calcium requirement for far away dry cows is relatively low: 0.6% of dry matter intake. This requirement can generally be met by the typical Southland wintering rations.

CLOSE UP DRY COW

The close up dry cow period is the most important phase of the entire lactation. How cows are managed in the three weeks leading up to calving will directly impact the productivity, health and reproductive efficiency of the entire lactation to come. The calcium requirement during this phase is 0.7% of dry matter intake. This level of calcium is typically provided by the wintering rations in Southland.

Please note: Supplemental calcium should NOT be fed during the Close Up Dry Cow phase.

CALCIUM

Mineral nutrition management during this phase can have a direct impact on the incidence of metabolic disorders, especially milk fever at calving.

By minimising the amount of calcium in the diet in the three weeks leading up to calving, stimulates the calcium metabolism in the cow.

The theory is that a minor decline in blood calcium concentration will stimulate parathyroid hormone (PTH) secretion, which in turn stimulates bone resorption and the production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.

This increases the draw of calcium from the bones, reduces the loss of urinary calcium, and stimulates the intestine to increase calcium absorption efficiency from the dietary calcium supply.

Preparing the cow for the increased calcium demand by switching on calcium metabolism prior to calving avoids the two to three day lag it can take to activate these mechanisms in the fresh cow and helps to avoid milk fever. With this process ‘switched on’ the drain of calcium at calving is more easily replaced when calcium is supplied in the milking ration.

MAGNESIUM

Magnesium should be included in the diet at a rate of 0.45% of dry matter.

If magnesium is limiting (hypomagnesemia), it will increase the risk for milk fever as magnesium plays an important role in switching on bone calcium resorption.

OTHER RECOMMENDATIONS

The other strategy to mitigate milk fever is to reduce dietary cation content (particularly potassium, K) of the ration as well. For example, Close Up Dry Cows should not be on effluent paddocks or paddocks recently fertilised with potash.

To ensure the balance of nutrients and minerals are optimal for the Close Up Dry Cow, review of the entire ration including the Dietary Cation-Anion Difference (DCAD) with your nutritionist is advised.

COLOSTRUM & FRESH COWS

The requirement for calcium increases four-fold (400%) on the day of calving

All cows develop some degree of hypocalcaemia at calving and for 10 days into the lactation

In order to mitigate the negative calcium balance the objective should be to prime calcium metabolism pre-calving AND ensure that all cows are adequately supplemented with calcium and magnesium immediately after calving

The ration should include 1.1% of calcium on a dry matter basis.

MID & LATE LACTATION

During early lactation, it is suggested that 800 to 1300g of calcium is removed from the bone to support milk production; this is 13 – 22% of a cow’s total skeletal calcium

The cow has a store of approximately 6000g of skeletal calcium. This calcium is restored to the bone during the last 20 to 30 weeks of the lactation and during the dry period

It is imperative to replace the mined calcium, from the bones, during the mid and late lactation with adequate dietary calcium

Adequate calcium requirements in New Zealand’s grass are often not met and this is particularly true during phases of rapid grass growth such as the spring and autumn flush periods when calcium and magnesium uptake in the grass is limited

It must also be acknowledged that in situations where pasture may be limiting and other feed sources (i.e. PKE and whole crop cereal silage) are used to meet dry matter intake demand, calcium deficit may be further exacerbated.

Calcium should be included at 0.8% and 0.6% of the mid and late lactation dry matter intakes, respectively to prevent autumn flush milk fevers, assist in the reduction of late lactation mastitis, to aid in the development of strong, healthy hooves, and to ensure enough calcium for re-mineralisation of the bones

BENEFITS OF SUPPLEMENTAL CALCIUM AS PART OF A BALANCED RATION

Stimulates appetite post-calving

Decreases downer cows

Optimises body condition post-calving

Drives peak milk production sooner and higher

Improves reproductive performance

Bolsters immune function

Helps mitigate mastitis and uterine inflammation

Replenishes calcium stores drained through the period of negative calcium balance (i.e. calving and peak lactation)

Ensures enough calcium for milk production and calcification of the foetal bones in mid to late lactation

Promotes hoof hardness to help mitigate lameness

CALCIUM STATUS

Calcium status in lactating dairy cows can be partitioned into four phases;

calcium deficiency

sub clinical deficiency

adequate status

no additional benefits.

CALCIUM DEFICIENCY

During the onset of lactation and through the colostrum production phase, all cows experience a degree of calcium deficiency

The large draw of calcium into the milk causes a sudden loss of calcium in the body resulting in acute hypocalcaemia (Milk Fever).

The degree and extent of hypocalcaemia will be a function of how well the calcium metabolism mechanism was primed in the Close Up Dry Cow phase and the degree of calcium supplemented in the diet at the onset of lactation.

SUBCLINICAL CALCIUM DEFICIENCY

It is interesting to note that because of the body’s drive to maintain adequate calcium levels, even in severely compromised animals, blood calcium levels will only be slightly lower than normal.

If dietary calcium is limiting, cows will pull calcium from her bones to maintain the calcium in the blood and milk. If there is not enough calcium in the diet, she will continue to put calcium into the milk, but will reduce milk yield.

There is a strong correlation between sub clinical hypocalcaemia and the incidence of retained foetal membranes, metritis, reduced fertility, mastitis, calving difficulties, reduced rumen fill, displaced abomasum, fatty liver, and ketosis.

In young calves, inadequate calcium supply in the diet will result in retarded bone growth